Jar with Feather Motif (1943-1953) is a strikingly beautiful object made in the mid-twentieth century. Its maker, Maria Martinez (1887-1980), became world-renowned for her black-on-black pottery and is regarded as one of the most important Native American ceramic artists of the twentieth century. Maria’s distinctive pottery was developed with her husband, Julian (Pocano) Martinez (1879–1943), based on ancient ceramics made by her indigenous ancestors. They were of Tewa heritage of the San Ildefonso Pueblo in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, present-day USA. Many of Maria’s family members were involved in pottery and she learned to make pots by watching her maternal aunt, Nicolasa Peña, and grandmother, Martina Montoya. By the age of thirteen, she was already celebrated for her skill. Traditional Pueblo ceramics, like many world pottery traditions, were a family and community endeavour undertaken mostly by women. Most often, each step in the process (pottery building, polishing, painting, and firing) was carried out by a different family member. It was a collective activity rather than one of individual artistic expression.

Maria worked with her sisters before she married, and then subsequently with her husband, Julian. Maria built and shaped the pots and Julian painted the designs. He was the first acknowledged male artist of their Pueblo to do so. Together, they revived techniques and motifs found on ancient pottery excavated in the region. They collaborated with Dr Edgar Hewett, archaeologist and director of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In 1908, Hewett had excavated some seventeenth-century black pottery shards and encouraged Maria and Julian to experiment with various firing and painting techniques inspired by ancient artefacts. Whilst helping Maria alongside subsistence farming, Julian became caretaker at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe. Maria and Julian studied the pottery in the display cases, observing form, motif, and technique. By 1921, they had mastered the process of making pottery with a highly glossed finish and matte-black designs. They found that smothering a cool fire with dried cow manure trapped the smoke, and that by using a special type of paint on top of a burnished surface, in combination with trapping the smoke and the low temperature of the fire, resulted in turning a red clay pot black.

Jar with feather motif, Maria Martinez, 1950 c. – 1950, New Mexico, Rio Grande Valley, United States of America, Sainsbury Centre Collection

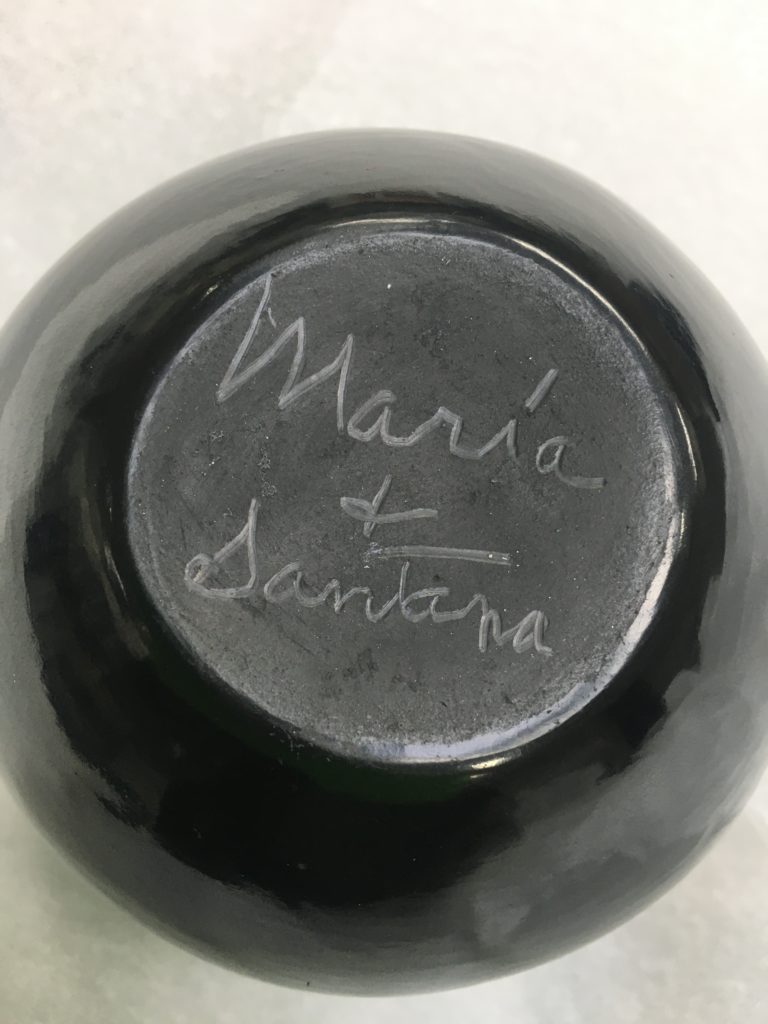

When Julian died, Maria worked with her daughter-in-law, Santana Roybal (1909-2002), as in Jar with Feather Motif. The jar is signed ‘Maria & Santana’ and would have been made between 1943 and 1953. This beautiful jar was hand-built using a coil technique. Maria gathered the clay and mixed it with locally sourced sand. She pinched together the snake-like coils of clay to create the basic shape of the pot. She then scraped and smoothed the coils with a gourd tool until the pot was the same thickness all the way around. When it was dry enough to handle, a thin layer of slip (watery clay) was applied over the pot, and then the surface was polished using a smooth, fine-grained stone. Once the jar had dried and hardened, she polished its surface with a small stone to create a burnished finish. Santana painted the feather and ziggurat design with liquid clay, producing a matte surface that contrasts with the highly polished areas. During the firing process, the oxygen supply was cut off, producing carbon smoke that turned the jar black.

Jar with feather motif, Maria Martinez, 1950 c. – 1950, New Mexico, Rio Grande Valley, United States of America, Sainsbury Centre Collection

By the mid-1920s, Maria’s black ware had become extremely popular outside the pueblo, thanks to a book published by Hewett. She was encouraged to sign her pots, becoming the first Pueblo potter to do so. They began to be regarded as works of art rather than household or ritual vessels. This coincided with the rise of the modernist aesthetic and growing European interest in the authentic indigenous artist. Her work was celebrated at art shows, expositions and fairs nationwide. Despite achieving great prominence, Maria eschewed the European notion of the isolated artistic genius, stating: ‘I just thank God because [my work is] not only for me; it’s for all the people. I said to my God, the Great Spirit, Mother Earth gave me this luck. So, I’m not going to keep it.’

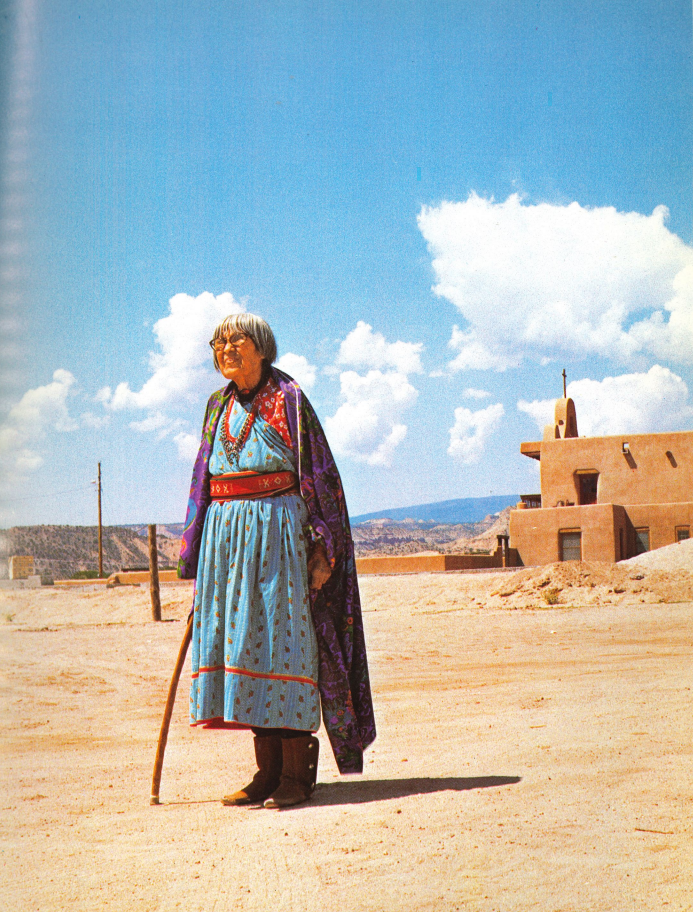

Maria was deeply connected with her pueblo of San Ildefonso, its traditional way of life, its ceremonies, and religious activities. Even when internationally celebrated, she preferred to remain in her ancestral home and community. Her important work can be found in major art museums worldwide and we feel very fortunate to have an astonishing piece in our Sainsbury Centre Collection.

Calvin Winner, November 2022

Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, Maria Martinez polishing pottery, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, Wyatt Davis, 1938, Negative Number: 044192