‘The idea of ‘paradise’ is often understood as being heteronormative’: In conversation with Yuki Kihara

The Sainsbury Centre presents Darwin in Paradise Camp, a new exhibition by Yuki Kihara. The exhibition features the UK premiere of Paradise Camp (2022), alongside original works by Paul Gaugin and a newly commissioned video work, Darwin Drag (2025).

Sainsbury Centre press officer, Kate Wolstenholme, sat down with Kihara to chat about about Paradise Camp.

Yuki Kihara, 'Two Fa'afafine on the Beach (after Gauguin)', 2020, c-print. Copyright: Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

Yuki Kihara is an interdisciplinary artist of Japanese and Sāmoan descent. Through a research-based approach, her work seeks to challenge dominant and singular historical narratives through a wide range of mediums, including performance, sculpture, video, photography and curatorial practice. The photographic series, Paradise Camp, was first presented at the Aotearoa New Zealand Pavilion in the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022.

Yuki Kihara. Image: Ralph Brown

KW: Can you give a background on yourself and your practice?

YK: I wanted to attend an art school, but my parents wouldn’t let me do it because they said there was no money in it, so I decided to enrol into fashion school where I saw fabrics as a sculptural material.

After I graduated fashion school in the mid-90s in Aotearoa New Zealand, I initially began working as a costume designer for various productions including theatre, dance, music videos, television and film before becoming a producer, director, actor, presenter, writer, and a choreographer – to name a few.

Having a socially engaged practice and working in an interdisciplinary manner meant that I wanted to be around people to collectively and collaboratively work on a project.

Almost 20 years later, I had the honour of representing Aotearoa New Zealand as the first Pacific Islander and the first Sāmoan Fa’afafine artist at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022 with my solo exhibition entitled Paradise Camp curated by Natalie King.

The photographic production of Paradise Camp involved a cast and crew of close to 100 people in Upolu Island, Sāmoa staged in March 2020 a few weeks before the global lockdown. Paradise Camp was Sāmoa’s biggest production to date, and I’m glad that the production gave us an opportunity to showcase local talent in the island.

Yuki Kihara, Fonofono o le Nuanua: Patches of the Rainbow (after Gauguin), 2020, C-print. Copyright: Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

KW: And how did that feel?

YK: I proposed to show Paradise Camp as the exhibition that represented Aotearoa New Zealand at the 59th Venice Biennale because I knew that I could use this opportunity to highlight pertinent issues that were affecting those of us who were part of the third and fourth gender community in Sāmoa, pertaining to issues around climate change.

In Sāmoan traditional society there are four culturally recognised genders. There is ‘Fa’afafine’, meaning in the manner of a woman, used to describe those like myself – assigned male at birth, who express their gender in a feminine way.

There are those that are ‘Fa’atama’, meaning in the manner of a man, who are assigned female at birth, but express gender in a masculine way.

Then there is ‘Tane’, meaning a cis-gender man and ‘Fafine’, meaning a cis-gender woman.

In the traditional village context, the Fa’afafine and Fa’atama are assigned the role of caregiver, and we look after young children and the elderly. Through our contribution in the community, all the four genders come together to build the resilience needed to take on any challenge.

However, it was through the process of colonialism that the binary was imposed, and we, the Fa’afafine and Fa’atama became excluded. Our collective resilience weakened and got broken, and as a result, the gender of Fa’afafine and Fa’atama is yet to be legally recognised. Today, the policies and legislations around climate change in Sāmoa are most often written in a binary way that excludes the Fa’afafine and Fa’atama’s contribution.

In Paradise Camp I wanted to reclaim the fictions of Paul Gauguin, and his portrayal of the Pacific region. I inserted a new narrative by imagining a Fa’afafine and Fa’atama Paradise – where no one is judged for their gender and sexuality and living in harmony with nature. I hope one day that Paradise Camp can be a reality in Sāmoa.

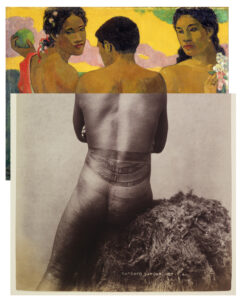

Three Tahiti(Sāmo)ans [After Gauguin]’ 2017 by Yuki Kihara

KW: Can you explain how 19th century French painter Paul Gauguin influenced Paradise Camp?

YK: Paul Gauguin’s paintings strangely reminded me of people and places in Sāmoa.

I then decided to conduct research where I compared the paintings of Gauguin, produced during his time in French Polynesia, against photographs of Sāmoa taken by New Zealand colonial photographer Thomas Andrew – and I was struck by their similarities.

Although Gauguin never came to Sāmoa, I believe he used photographs from Sāmoa as a foundational reference for the development of his major paintings – which he passed it off as being Tahitian and Marquesan.

For example, the silhouette of a tattooed man featured in a Thomas Andrew photograph has been lifted in a painting entitled Three Tahitians. When you merge the photograph and the painting as a collage, you can see that Gauguin lifted this photograph and called it Tahitian. This is alluded to my work entitled ‘Three Tahiti(Sāmoa)ns’ (2022).

When I realised the direct and indirect link between Gauguin and Sāmoa – and how he appropriated photographs from Sāmoa and passed it off as something else – it gave me the reason to reclaim the narrative by inserting a new narrative through the process of ‘upcycling’ 12 paintings by Gauguin which I felt was inspired by Sāmoa.

Upcycling means you take something old, and you improve it. So, my photographs are an improved version of Gauguin’s paintings.

I decided on the medium of photography for the Paradise Camp series for few reasons. When a photographic image is in soft-focus it often reminds me of an impressionist painting which is what Gauguin paints. However, when a photographic image is in focus where the soft-focus ‘fog’ is removed, that image appears sharply which to me alludes to clarity. The way that the Paradise Camp photographic series is presented is to provide clarity to exactly where the inspiration behind select Gauguin paintings came from – which is from Sāmoa.

Paul Gauguin, Bathers at Tahiti, 1897. Courtesy of Barber Institute, Birmingham

KW: Where did the title Paradise Camp come from?

YK: The idea of ‘paradise’ is often understood as being heteronormative.

In the Sāmoan context, the word ‘paradise’ was introduced through the Bible, and it describes a lush landscape occupied by Adam and Eve – who are a cis-gendered couple. By using the word ‘camp’ next to it, it queers the idea of heteronormativity and allows for more nuanced understanding what paradise could be.

In Sāmoa, we rely heavily on these images of paradise for tourism, but as locals, we sometimes look at these tourism campaigns with a bit of parody and a cliché to a point of becoming kitsch and a performance put on for the tourists. The tourism campaigns in the Pacific are also heteronormative where they would never feature Fa’afafine and Fa’atama, as if to hide us away from the mainstream public to avoid ridiculing our country.

In Paradise Camp, I wanted to lift the veil by referencing the visual language of tourism that’s often associated with the romantic aesthetic of Gauguin’s paintings.

KW: What is it which drew you to the Sainsbury Centre?

YK: One of the criteria’s that I’ve set for the touring of the Paradise Camp exhibition is that the host of the exhibition must have gender neutral bathrooms installed to show their commitment to inclusion of all audiences. I made the Paradise Camp exhibition to empower people like me, who are Fa’afafine, trans and non-binary peoples – so the last thing I want to do is for them to feel marginalised within an institution that enforces gender binary through their bathrooms.

I believe that if museums and galleries are supporting an exhibition then their support must extend beyond the scope of an exhibition by engaging with its own internal structures.

I also knew of the work of Dr Karen Jacobs and Professor Steven Hooper from the Sainsbury Research Unit and their rapport with Indigenous Pacific people.

My conversations with curator Tania Moore have helped to deepen my understanding about the Sainsbury Centre, their collections and their willingness to engage in constructive critique through art and participation.

Darwin in Paradise Camp: Yuki Kihara will be on display 15 March to 3 August 2025.