Influences on the abstract

The artist Mary Webb has had a long relationship with the Sainsbury Centre and UEA, going back to 1970 when the University acquired its first painting. Mary is one of the most important abstract painters of her generation and her work features in the new Sainsbury Centre exhibition Rhythm and Geometry: Constructivist art in Britain since 1951. Here, Head of Collections Calvin Winner talks to her about her formative years and meeting with Sonia Delaunay in 1962.

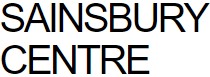

Mary Webb in her studio, Norwich School of Art, 1967. Photo: Ed Middleditch

As a child, did you look at art?

I would go to exhibitions with my mother. I remember the Van Gogh at the Tate (1947) making a vivid impression. Later, looking for work during the school holidays I had put a card in the local newsagents looking for a job as a babysitter. I got a reply from Phyllis Lawson, an artist, looking for a model. She was a pupil of Joseph Herman. She introduced me to him, and besides modelling for her I modelled for his drawing class after school.

And you went to Newcastle in 1958 to study Fine Art?

Yes, I applied to Reading and Newcastle and was accepted at both. I was impressed with Newcastle. I sought the advice of my art teacher, Nommie Durell, who lived in Hampstead. She looked through the Newcastle prospectus and was adamant I should go there, as there were so many good people teaching there: Victor Pasmore, Laurence Gowing, Richard Hamilton, Quentin Bell.

Mary Webb, painting studio, Newcastle, 1962. Photo: Derek Morris

Can you tell me about Laurence Gowing, the celebrated Principal of Newcastle, which at the time was a department of the University of Durham?

He was a formidable presence, had a loud voice and a stammer, but in fact was very articulate. In my first term I went to a criticism he gave on work the second-year painters had done over the summer. It was a wonderful talk, and I found it very inspiring. But one could see his influence in the Euston Road style work going on the studios. I was shocked on one occasion to find three girls sitting side by side all doing identical paintings with four little brush strokes going in one direction and then in another. I made a mental note never to go down that path!

Can you tell me about the The Basic Course, the teaching method at Newcastle, influenced by the Bauhaus and devised by Pasmore and Hamilton?

The Basic Course lasted for the first year. Coming straight from school where the emphasis had been traditional, I found it difficult to grasp the intention behind the exercises we were set by Victor. One day a week we were taught by Richard Hamilton. Again, I wasn’t very quick to assimilate this new approach to visual language. Richard was patient, and much easier to talk to then Victor. I had a copy of the Evergreen Revue on my desk, and he noticed and discussed it. I was impressed that he was familiar with it.

Retrospectively the basic course exercises made sense but I wasn’t ready for them at the time. So I slipped away to the Life Room. Richard took an interest in what I was doing in the Life Room and was encouraging. He and his wife Terry were very hospitable, and in my third year invited me over for gatherings at their house in Highgate. There was always an interesting mix of people there, people from the Independent Group, artists and designers.

One can’t talk about Newcastle at that time and not mention the parties. The arrival or departure of a member of staff was cause for these well-choreographed affairs. These were held in Richard’s studio. An “All hail to the New Professor Party” was held for Kenneth Rowntree’s arrival, and a wonderful leaving party for Victor Pasmore with a review which involved Jack Shepherd dressed as an army major complete with baton using a facsimile of one of Victor’s paintings as a battle plan.

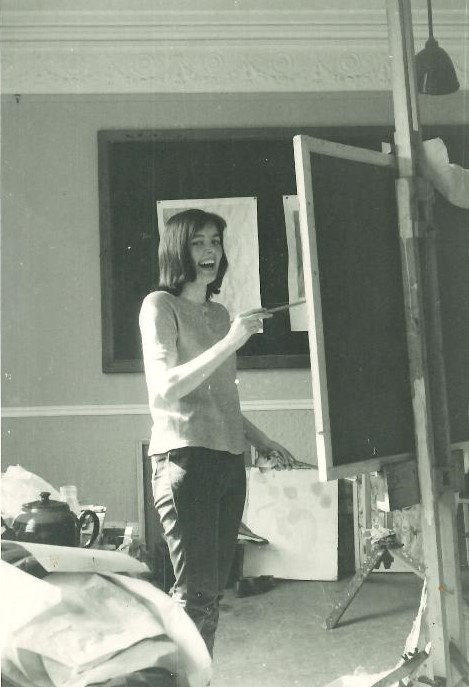

Mary Webb's tutor, the artist Richard Hamilton in front of one of his iconic relief paintings of the Guggenheim Museum, photographed at Newcastle, 1964. Photo: Mary Webb

Victor Pasmore was one of the most important abstract British artists at the time. What was your experience of him?

I had come across the Penguin English Painters series and the volume devoted to Victor while I was at school. It was another reason to choose Newcastle. His paintings of Hammersmith, and those of his pregnant wife were stunning. I wanted to paint like that! One was very much in awe of him, and conscious that one was in the presence of a practising artist who was actually working in school. In fact all the staff had studios, an atelier system that gave the place a head of steam. But I did find the group criticisms held by Victor sometimes confusing, he would latch onto a word, and apply it to everyone’s work. On one occasion he found everything an “approximation”. One learnt most from looking at his work.

And there was an art school trip to see the famous New American Painting Show at the Tate in 1959?

Yes, that was in my first year. It was a special coach trip organised by older students. It was mind blowing and very exciting to see abstract work on that scale. I remember in particular the work of Sam Francis, his colour stood out. It gave one the possibility of working with colour on a grand scale.

Mary Webb, painting studio, Newcastle, 1962. Photo: Derek Morris

What about fellow students. Derek Morris, Rita Donagh, John Walters and Mark Lancaster?

Derek Morris became a lifelong friend having met at interview. Rita Donagh was very special, an outstanding talented painter. John Walters had a love of jazz and led a very good band. Mark Lancaster worked a lot for Richard (Hamilton) and became his right-hand man. He went to New York and Richard (Hamilton) had given him Andy Warhol’s phone number. He was invited to the Factory, where apparently they were making a Dracula movie. He stayed on and worked with Warhol on the screen prints.

What other artists’ work did you look at?

I became very interested in the work of Jack Smith. He painted a series “light passing over objects”, seemingly giving the same weight to the space between objects as the objects themselves. This was something that intrigued me and by my fifth year I began to realise that I was putting as much emphasis on the space around the model as the model herself. The model was becoming irrelevant.

The Rainbow Project at Newcastle, 1963 with artist Richard (Dick) Smith (second from the left, back row). Mary Webb (bottom right) with fellow students. Photo: Richard Hamilton

And what about the artist Richard Smith, he was important to you?

Yes enormously so. Richard (Hamilton) invited him up to do a project with a group of students for a week. Knowing my interest in colour and the Delaunays, Richard suggested I join in. Dick (Richard Smith), who was a visiting tutor, got us to make a rainbow out of coloured tissue, drape it over a frame and treat it as a still life. It was an inspiring week just dealing with colour, and it would eventually give me the confidence to start working non-figuratively. Dick invited me to his loft studio in Old Street. He was working on shaped canvasses that referenced methods used in advertising, colour played an important part. In 1963 we spent some time together going to exhibitions and openings.

And whilst still a student, you discovered the work of Robert Delaunay?

Yes – around 1961 Eric Dobson, my tutor, suggested I go and look at a drawing by Robert Delaunay in a travelling exhibition in the Hatton Gallery at the Art School. I was intrigued and found a book on him in the Art School library. I remember sitting on the Art School roof garden looking through the book and getting very excited by the images. Colour was being used in a totally abstract way.

And as a part of your development as an abstract painter you decided to write your dissertation on Robert Delaunay?

Yes, I had thought of doing it on Bonnard, but after discovering Delaunay I decided on him. I found an article by Pierre Francastel. There was an account of a talk on colour given by Delaunay, where he described how the energies and interaction of colours could create movements within a painting. Francastel went on to say “Felt space which is the domain of the painter is essentially coloured”, a statement I could instantly relate to.

Mary Webb in Paris to visit Sonia Delaunay, 1961

So you decided to make contact with his widow, fellow artist and the co-founder of the Orphism movement, Sonia Delaunay?

I didn’t have her address so I wrote to Pierre Francastel and received a letter from Sonia to say she would be happy to receive me in Paris. She lived in a beautiful Art Deco studio apartment in the Rue St Simon on the left bank. She was a formidable presence but welcoming, with a dry sense of humour, and was very patient in answering all my questions. She always started the conversation in French. Her English was impeccable, and my French not as good as her English so we would soon relapse into English.

I went back to see Sonia the next summer. I took a couple of small paintings with me and she suggested I exhibit with a group Nouvelles Realities! But, I was still only a student and about to run out of my grant so did nothing about it. However, when I was teaching in Norwich I decided to contact her again and she introduced me to her dealer, Jacques Damase. I made regular trips to Paris and Jacques showed some of my prints in his Gallery in the Rue de Varenne. On a visit to London, Jacques and Sonia came to my studio in Streatham. Sonia bought one of my screen prints and Jacques gave me a print of Sonia’s design for a scarf for Jaques Heim.

Sonia Delaunay in her studio in the Rue St Simon, Paris, 1969. Photo: Mary Webb

You were fortunate in your choice of art education at Newcastle following the advice of your school art teacher?

Yes, I was, and one thing I am particularly proud of in relation to Newcastle is the decision of the University in 1967 to award Martin Luther King an honorary doctorate in civil law. This was just months before he was assassinated. He attended the ceremony and made a wonderful speech, warmly thanking the University for supporting what he described as his “humble efforts”.