Are we ready to swim in a watery world? Learning from our North Sea Neighbours

Ahead of the Sainsbury Centre’s ‘A World of Water‘ show, we travelled to the Netherlands in partnership with the Netherlands Board of Tourism and Conventions, to learn from our North Sea neighbours, highlighting the themes of the exhibition in reality.

By Kate Wolstenholme

Looking out to the North Sea from the Zandmotor Beach in the Netherlands

There was once a time where it was possible to walk across from the Netherlands to Norfolk, but now, this once-dry passage linking the UK to our North Sea neighbours, is the source of an uncertain and strikingly precarious future for our lands.

With 26% of the country lying below sea level – the lowest point being 22 feet (6.7 meters) – the Netherlands is at risk of its land flooding entirely, and this urgency of our changing world is a harsh reality.

Reimagining the role of a museum in the 21st Century, here at the Sainsbury Centre we ask some of the biggest questions facing our society, investigated through artwork from all over the globe. This spring, the Centre asks: Can the Seas Survive Us?

The United Nations describe the oceans as “overwhelmed” as humans overfish, pollute, and destroy habitats, with the ocean’s health declining at an “alarming rate”. Taking the North Sea and the historical relationship between Norfolk and the Netherlands as its starting point, one of our featured exhibitions, A World of Water, looks at the human impact on the sea.

Rather than walking across the land between the UK and the Netherlands as the mammoths would have done, I woke up in the Hook of Holland after being gently rocked to sleep onboard the Stena Britannica. For the next three days, I cannot escape the sight of water, as land and water interweave dominantly through the Dutch landscape.

Portrait of Mate Master Richard on the Stena Britannica’s bridge.

A looming presence of water is constant reminder of how quickly things can change. Research projects such as the Institute for Water Education and innovative coastal protection measures such as the Sand Motor Project show there to be a compulsory determination to remain at home on this land, whilst projects such as the Urban Waterbuffer Cromvlietpark in The Hague, which utilises the 35km4 existing aquafer below its surface to aid the community, shows a passion to work in unison with surrounding water.

On a visit to his studio, Rotterdam-based artist Boris Maas described how his work The Urge to Sit Dry was “risen out of panic” as a “symbol of safety” in a city of which 90% is below sea level. This chair, of which one of the eight in existence sits at the round table of the First Minister of Climate, is often site-specifically moderated to show how high one is required to sit in order to be above sea level at the given location.

At the artist’s home, this is two meters.

Artist Boris Maas in his studio with ‘The Urge to Sit Dry’

Visiting Anastasia Eggers, another Rotterdam-based artist who also features in A World of Water, she talked us through the origins of her audio-visual documentary project Brexit Herring, how the herring stock in the North Sea is reducing, in part due to the temperature of the water rising and schools heading further north. Following fishermen from Lowestoft, Eggers noticed parallels between how humans and fish behave, describing both as “one big entity”. Just as the herring are overcoming a change to their habitat, so are humans – in ways like sitting dry at height.

Artist Anastasia Eggers in her studio with work from ‘Brexit Herring’

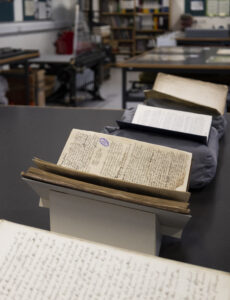

An interchange of inspiration and skills has long existed across this patch of the North Sea. The Dutch Orders and Dutch and Walloon Strangers Book document the arrival and regulation of Dutch and Walloon migrants to Norfolk and will be on display in the exhibition on loan from the Norfolk Record Office.

Their innovations in weaving, farming, and flood management reshaped East Anglia and left a lasting legacy to this day. Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden led large-scale drainage projects in the Fens, reclaiming vast wetlands and transforming the landscape, much like the polders in the Netherlands.

Dutch Orders and Dutch and Walloon Strangers Books at the Norfolk Record Office

Maps at the Norfolk Record Office

A World of Water also features a salon-style hang showing how significantly East Anglian master painters, including the Norwich School of Painters, were inspired by their friends, the Dutch masters.

But the relationship between the UK and the Netherlands is more than human. In Norfolk, winter storms stir the seabed, sending mud plumes across the North Sea toward the Netherlands. This natural process reflects the deep cultural, historical, and economic ties between the two regions and contributes to the protection of the Dutch coastline.

Upon visiting the Nieuwe Instituut, the national museum for architecture, design and digital culture who describe themselves as “the testing ground for the future” embracing our world, we are reminded and asked: are we ready to swim in a water world?

Here we viewed Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld’s Ontwerptekening badmuts (Design drawing swimming caps) before they get packed to travel over for A World of Water. The renowned Dutch architect and designer reinterpreted the swimming cap, drawing inspiration from coral, eels, and fish. His designs blend art, nature and functionality, urging us to reconsider design’s role in sustainability.

Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld’s ‘Ontwerptekening badmuts’ (Design drawing swimming caps) at the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam

Architecture and design could shape this resilient future – and has been in Dutch thinking for generations. Also held at the Nieuwe Instituut, and travelling to the Sainsbury Centre for the exhibition, is a 1973 model by Dutch architects of the Zeckendorf House for an island in the Bahamas which features an extension overhanging a reef. Though unrealised, it prompts reflection on how architecture can adapt to rising seas, just like where we had dinner. Putaine, situated in Floating Office Rotterdam is an architectural project created out of the real possibility that if the water level rises due to climate change, it will float.

I am left with a sense of fear and urgency, but more so with a determined inspiration to live with, and not against, our seas and adapt to our transforming world.

With thanks to the Netherlands Board of Tourism & Conventions and Stena Line.