Earlier this month, the Sainsbury Centre added 29 important works by the British sculptor and draughtsman Elisabeth Frink to its collection – an acquisition that will help secure the artist’s legacy as one of the 20th century’s great sculptors. The move accompanies a wider resurgence in Frink’s reputation, which began when the Centre presented a major retrospective in 2018. Head of Collections and curator of the exhibition, Calvin Winner, comments “Frink’s work aims to reveal universal truths”.

Elisabeth Frink’s Universal Truths

Why this artist’s works will be right at home in the Sainsbury collection

Elisabeth Frink photographed by Edward Pool, c.1964–65. Photo: Frink Estate and Archive, Dorset History Centre

Born in Thurlow, Suffolk, Frink is best known for her public commissions, which can be seen in streets, hospitals, religious buildings and other spaces across the UK. The acquisition, which brings together prints, drawings and sculptures reveals the complexity of Frink’s practice. It was made possible by her son, Lin Jammet, who worked on the early stages of the exhibition, only to pass away suddenly a year prior to its opening. Jammet shared the curator’s passion for finding a home for Frink’s legacy near her birthplace. After his death, Winner worked with former Frink estate curator Annette Ratuszniak to select a “powerful, representative” grouping of works that reveals the artist’s diverse thematic interests.

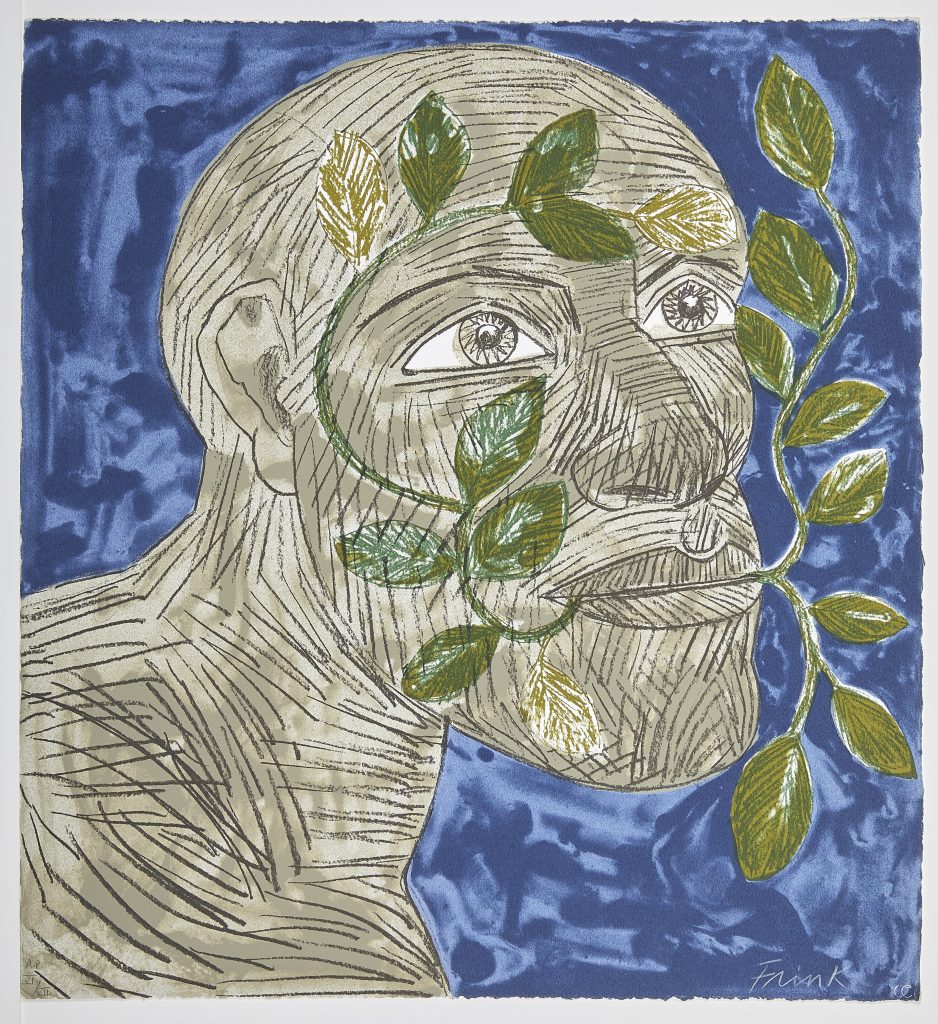

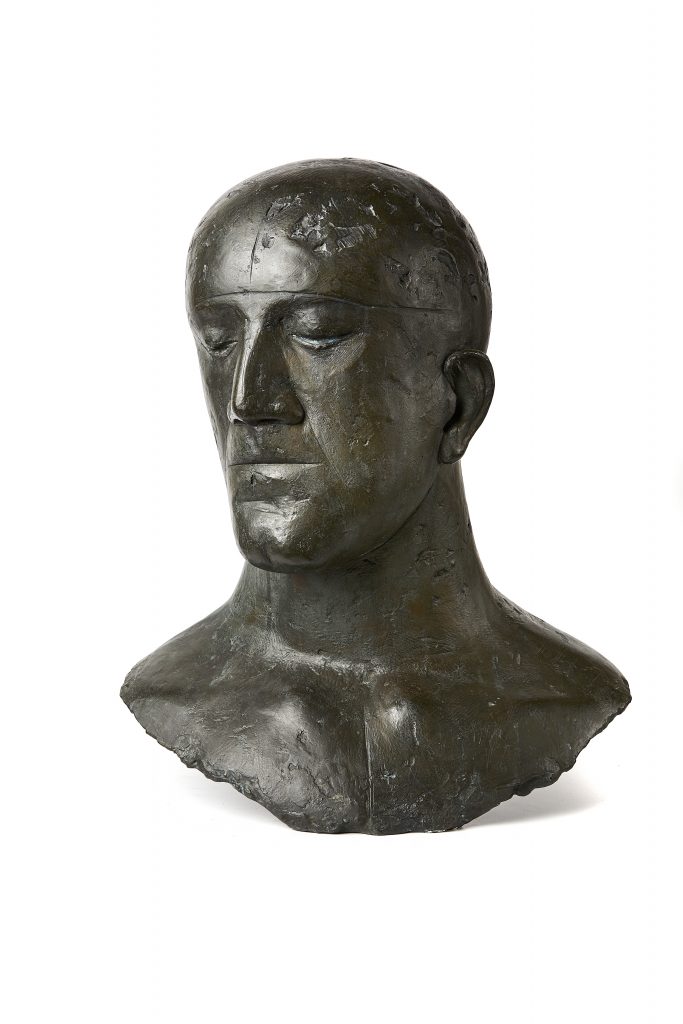

The result is a selection that spans 40 years of creativity, and that draws on the ancient yet “eternal” themes with which Frink was fascinated, says Winner. Goggle Head, 1969, and her Tribute heads, 1975, for example, represent opposing archetypes of human behaviour – one its evil, “flawed” nature and the other its selfless side. A bronze vulture she made as a graduate, meanwhile, reflects humanity’s longstanding relationship with animals, as do fantastical drawings from the 1960s and large, cloud-like Mirage sculptures that Winner says reflect “a more playful” side to her practice.

Underpinning each work is Frink’s ability to borrow from ancient themes to respond to her own life, and the events taking place around her. Bird sculptures embody the tensions of the Cold War, while human forms present the psychological aftermath of the Second World War, in which her father fought. Spinning Man II, 1960, part of a group of works she began making the year Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was preparing to go into space, “captures the excitement of that moment”, Winner says. “She’s not isolated in the studio,” he adds. “She was an artist who really responded to her time.”

Despite rave reviews in her early career, and the Tate buying a sculpture from her first show, after the 1950s Frink stopped being regarded as a “serious, critical artist” – a result of institutional sexism and a lack of state support, Winner explains. But now, the curator hopes the Sainsbury Centre will become a “study centre” for the artist, just like it is for others such as Francis Bacon, and that the shared interests between the collection and Frink’s work will make for a powerful union. “At the Sainsbury Centre, we look at the universal nature of art, and Frink very much fits into that picture,” he says. “Now, for anybody who’s interested in Frink, but also for future generations, her work will be visible.”

A display of Elisabeth Frink’s work is planned for once the Sainsbury Centre reopens to the public