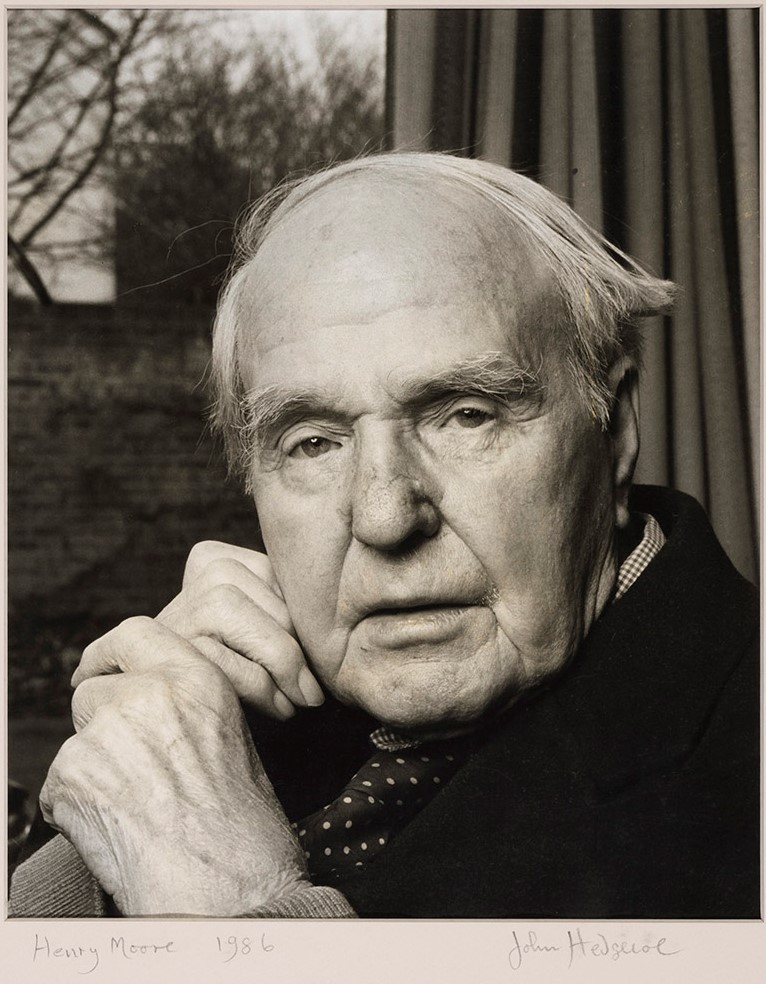

Introducing Henry Moore

Henry Moore was born in Castleford, Yorkshire, in 1898, the seventh of eight children. His father, Raymond Spencer Moore, was a coal miner, a socialist, a trade unionist, and a strong believer in education. The slag heaps and the craggy landscape around the town were an early source of inspiration that Moore still recalled years later.

Moore won a scholarship to the Castleford Grammar School, where he showed a talent for art and was much encouraged by his teacher, Alice Gostick. Although he had ambitions to be a sculptor from a young age, he was encouraged by his father to train as a schoolteacher, a more secure option for a working-class boy. He taught for several months before signing up for the army in the First World War. He was sent back to England after being gassed during the battle of Cambrai. In September 1919, he used his rehabilitation grant to go to the Leeds School of Art, where he studied for two years. In his first year at Leeds, Moore spent most of his time studying drawing, and drawing would remain a central part of his practice. At the end of his second year, he was awarded a Royal Exhibition scholarship to study at the Royal College of Art in London. He later taught at the college and it was there that he met his future wife, Irina Radetsky.

Moore used his time in London to study works in the city’s museums, particularly the British Museum, where he developed an interest in art and antiquities from Africa, Asia and the Americas. After completing his course at the Royal College of Art, travel scholarships allowed him to spend time in France and Italy, and his influences at this time include European modernism, particularly cubist sculpture, Mexican stone carvings seen in the Trocadero in Paris, as well as the Old Masters.

Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, Moore developed his own modernist style. He enjoyed numerous one-man-shows and commissions, and his reputation as a leading avant-garde sculptor grew.

He became part of Unit One, a group of young artists including Paul Nash, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, and the poet and critic Herbert Read. They were committed to promoting the international modern art movement in Britain. From the early 1930s Moore began to experiment with abstract forms which he combined with references to the human figure. His sketchbooks from the period show him making use of organic and natural forms.

He collected rocks, pebbles, shells, and bones. These he studied and drew, searching, as he put it, for “nature’s principles of form and rhythm” which he could apply to his sculpture. It’s at this time, that his interest in concavities and holes appear in his work, something that, alongside his experiments in abstraction, received a hostile reception from the British public when applied to the human form.

By this time, the Moores were living in Hampstead, described by Herbert Read as ‘a nest of gentle artists’. This dynamic avant-garde community included Barbara Hepworth, Paul Nash and Ben Nicholson; the European emigres Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy, and Marcel Breuer; and Herbert Read, himself. When the second world war broke out, Moore almost gave up sculpture completely. He became an official war artist. It was the sight of Londoners sleeping in underground stations during the air-raids that led to his now famous shelter drawings.

As a result of bomb damage to their London flat, the Moores moved to Hoglands, an ancient farmhouse at Perry Green, Much Hadham, in Hertfordshire. It was here that their daughter was born in 1946, and where Henry and Irina would live for the rest of their lives. Perry Green offered a peaceful rural setting in which he continued to explore the analogies between the body and the landscape. Over time, Moore extended the land and developed the outbuildings into studios. This enabled him to work on large scale works out of doors, and to create a sculpture garden of his own works in the grounds.

During this time Moore’s prestige continued to grow nationally and internationally. In 1941 he was appointed as a Trustee of the Tate Gallery. His first solo exhibition followed in 1945, and in 1946 the Museum of Modern Art in New York held the first major international retrospective of Moore’s work. In 1948 Henry Moore held a one-man show in the British Pavilion at the 24th Venice Biennale, where he was awarded the International Sculpture Prize. In 1951 the Festival of Britain was organised by the Labour government to promote the arts, science and industry and to further encourage optimism after the war. Moore’s ‘Reclining Figure: Festival’ was given a central position on the South Bank site. Moore said: “I think this is the first sculpture in which I succeeded in making form and space sculpturally inseparable.” To coincide with the festival, John Read produced a documentary titled Henry Moore for the BBC, making Moore the first ever living artist to be the subject of a film. In the same year Moore had his first retrospective at Tate in London.

By 1952, the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was presenting a new group of sculptors, dubbed by Herbert Read the ‘Geometry of Fear’ group, on account of their jagged, anxiety-ridden works. Moore, however, was still represented, this time at the entrance to the pavilion, suggesting his role as the forefather to the younger generation of sculptors on show. By this time, the negative, pre-war reception of his work in some quarters, had been replaced by a widely held view that he represented a new, more optimistic, post-war Britain. His works featured predominantly in urban regeneration and New Town projects, such as Harlow and Stevenage, in the wake of Labour’s 1946 New Town’s Act.

In the following years, Moore accepted many more major commissions nationally and internationally. He took on two or three young sculptors as assistants to help with the more laborious and time-consuming aspects of sculpting. He also made a large number of etchings and lithographs from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, many of animals and animal bones.

During his own lifetime Moore gained a reputation as a major modern artist, the first modern English sculptor to garner critical acclaim on the international stage. He is still widely regarded as one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century.

Moore died at Perry Green in 1986, aged 88. He was survived by his wife Irina (who died in 1989) and his daughter Mary.