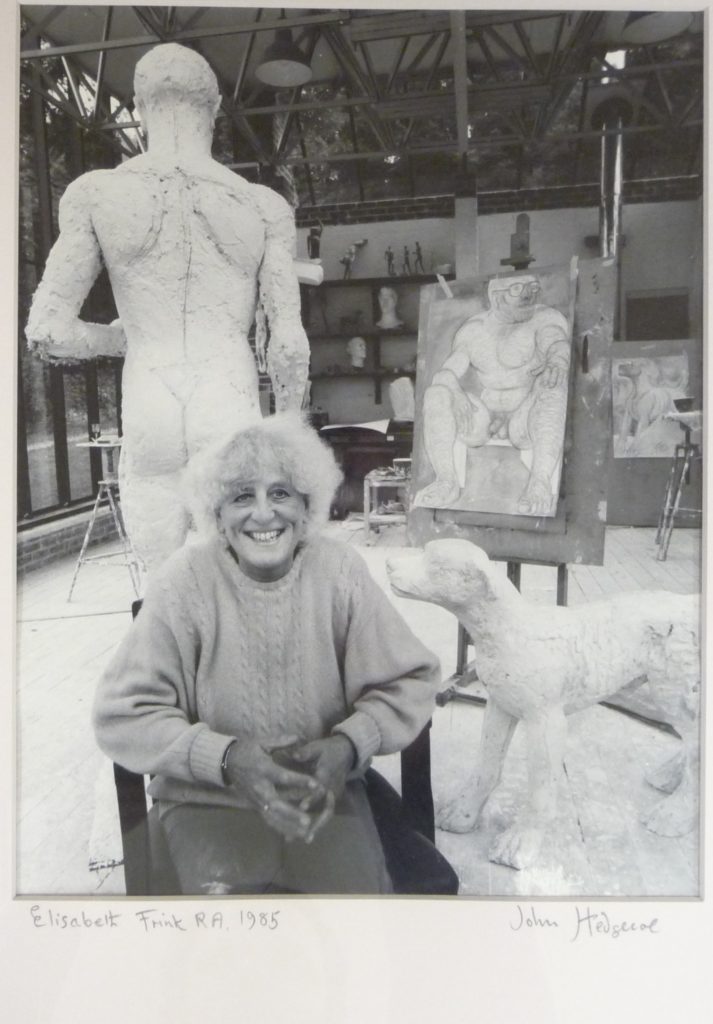

Introducing Elisabeth Frink

Elisabeth Frink was born in 1930 in Great Thurlow, Suffolk. Her father was an officer in the Royal Dragoon Guards. She was nine years old when the Second World War broke out. Their home was close to an airbase and she later recalled the trauma of the air-raids, and witnessing planes and airmen falling from the sky. She also recalled the impact of seeing physically and psychologically wounded soldiers returning from battle, a stark contrast to her idealised notion of the hero soldier represented by her father. In 1939, Frink, her mother and brother were evacuated to Exmouth in Devon.

From 1947 to 1953, Frink studied at Guildford and Chelsea schools of art where she was taught by Bernard Meadows and Willi Soukop. Frink started to make plaster sculptures of men and animals, which she later described as ‘very strange sort of gothic, apocryphal figures, very gloomy’. She achieved early success when, in 1952, whilst still a student at Chelsea, she was exhibited by the Beaux Arts Gallery in London. On the back of this, Tate Gallery purchased a work entitled ‘Bird’. She was still only 22 years old. As a result she was associated with an older group of postwar British sculptors including Reg Butler, Bernard Meadows, Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick, and Eduardo Paolozzi. This group were known as the ‘Geometry of Fear’ sculptors, a term coined by the art critic Herbert Read , on account of their angst-ridden work reflecting the traumas of the second-world war and the gloomy cold-war era with its growing fears of nuclear annihilation.

Frink went on to teach at Chelsea (1953-60) and St Martin’s School of Art (1955-7). Despite the gloomy atmosphere in 1950s London, the interest in British sculpture internationally was being established by Henry Moore, and Frink recalls lively and happy times among her network of artist friends. She drank in London’s bohemian pubs habituated by Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, John Minton and Michael Andrews, and was known for the wild parties she threw in her Chelsea flat. The subject matter associated with Frink throughout her career – men, birds, dogs, horses and religious motifs – were already present in her work, as was the distinctive rough surface of her sculptures. This was achieved by building up the form in plaster over an armature, then working and cutting into it with a chisel and a surform, a tool that planes and grates.

In the 1960s Frink’s continuing fascination with the human form was evident in a series of falling figures and winged men. Frink talked of ‘two themes of male figures… the basic male nude, in a sense, strong and powerful. Then there is the other one, which is more fugitive’. She attributed this paradox to her wartime experiences, hero-worshipping her soldier father, but seeing the vulnerability of wounded and falling airmen. Another experience she never forgot was seeing the first pictures of Belsen whilst still a teenager. While living in France from 1967 to 1970, she began a series of sinister male heads, the Goggle Heads. These evil aggressors were counterparts to her Tribute Heads, the victims of violence and oppression.

In 1971, Frink was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy. Now living again in England, she continued her focus on the male nude. Her iconic running men of the later 1970s seem to be both running to and running from something. As expressions of stoicism and struggle in the face of adversity, they continued her interest in the paradoxical mix of male sensuality, strength and vulnerability.

Throughout her career, Frink made sculptures of animals, in particular birds and horses, expressing a passion for wildlife that she attributed to her childhood in the countryside. As with her male figures, however, there are darker undercurrents beneath the beauty, recalling again the trauma of war. She likened her birds to bits of shrapnel, part organic, part machine. The hybrid figure is a recurrent motif in her work, blending man, animal and machine.

In the 1980s, The Royal Academy held a retrospective of Frink’s work and at the same time a catalogue raisonné was published. This led to four further solo exhibitions and several group shows. There was talk of Frink becoming the first female president of the Royal Academy, but she rejected this idea, saying that it would take her away from her busy career as a sculptor, although possibly there was also an unwillingness to become so fully representative of ‘the establishment’. Nonetheless, her status as one of the most important British Sculptors of the twentieth century was established.

Frink continued to produce a large output of work, taking on many commissions, and exhibiting regularly into the early 1990s, when a cancer diagnosis and surgery forced a pause in her schedule. Despite further surgery, she continued to work, returning as soon as she could to her studio between treatments. The Green Man head made at this time was a fitting symbol of fertility and the continuation of life, offering spiritual solace to the artist. Her last work was the large-scale Risen Christ, for Liverpool Cathedral. Dame Elisabeth Frink died the week after it was installed on 18 April 1993.