Lesson One – Moore, Sculpture and Nature

GETTING YOUR EYE IN

ACTIVITY 1

Whilst your observations are still fresh, jot down a quick verbal description of the piece. It doesn’t have to be formal. Don’t be afraid to use your own language – ‘the texture of a chewed pencil’ is fine, for example. As long as it captures your first impressions in a truthful way.

ACTIVITY 2

Now look again at Reclining Figure. This time, direct your attention to its parkland setting. If you have the app, you might want to look at the 180 degree videos, taken from three different viewpoints. Or you can work from the images below.

This time, notice specifically how the sculpture and the parkland setting work together. Look for echoes and contrasts in form and colour between the sculpture and the grass, trees and sky. Consider too, how the different weather on the days when these two photographs were taken changes these visual relationships.

Add any new observations to your initial description of the sculpture.

FROM THE ARTIST’S PERPECTIVE

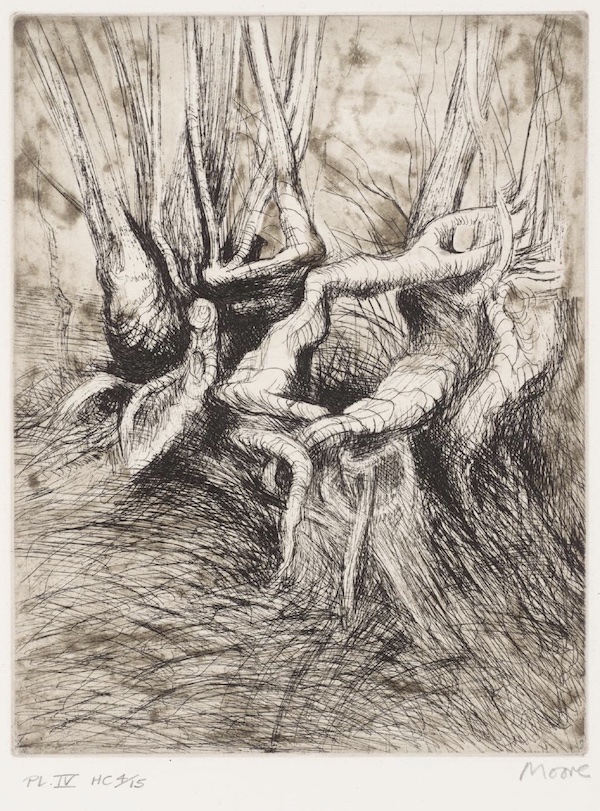

Now that you’ve had a chance to develop your own observations, let’s take a look at this selection of sketches, quotes, and photographs from Henry Moore, himself. As you browse through them, see what you can glean about his interest in the natural world, and its relationship to the human figure.

TIP: Don’t forget to use your visual observation skills. Note down any interesting visual echoes between his drawings of figures, bones and natural objects. And be really nosey when looking at the photograph of Moore in his Maquette Studio. This was his creative sanctuary, where he generated ideas for new works. Notice what he has around him for inspiration.

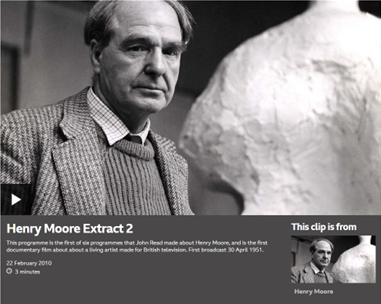

Etching, drypoint and aquatint in two colours

© Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

Pencil, ink, waterclour, chalk, wax crayon on paper.

“Beside the human form, I am tremendously excited by all natural forms, such as cloud formations, birds, trees and their roots, and mountains, which are to me the wrinkling of the earth’s surface, like drapery. It is extraordinary how closely ripples in the sand on the seashore resemble the gouge marks in the wood carving.”

Henry Moore, in Henry Spencer Moore, London, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1968

‘I realised what an advantage a separated two-piece composition could have in relating figures to landscape. Knees and breasts are mountains. Once these two parts become separated you don’t expect it to be a naturalistic figure.’

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture , Macdonald, London, 1966, p.266

“Flintstones, peoples, shells and driftwood have all helped me to start off ideas, but far more important to me has been the human figure and its inner skeleton structure . You can feel that a bone has had some of use in its life; it has experienced tensions, has supported weights and has actually performed an organic function… In themselves peoples are dead form, their shape is accidental, and merely to copy them would not in itself create a sculptural form. It is what I see in them that gives them their significance.”

Henry Moore, in Henry Spencer Moore, London, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1968

Sainsbury Centre Collection. Donated by Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, 1973.

© Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

Sainsbury Centre Collection. Donated by Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, 1973.

© Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundatio

So we can see from these sketches and quotes that Moore saw strong visual correspondences across a whole range of natural forms: bones, pebbles, patterns in sand, the grain in wood, the human body, roots, and branches of trees. Putting these images together, it is interesting how new connections emerge – between the tree roots and the hands in the shelter drawings, for example.

And did you notice all the different objects in his studio, and the echoes between skulls, bones, and his plaster models?

Equally interesting, is how, in the quotes, he gives priority to the human figure. I think there are two important clues here. First, he tells us something important about why he relates the human body to the landscape: because it helps the viewer move away from the expectation that the figure will be naturalistic. So this is something to do with his process of abstraction. Secondly, his insistence that the natural form can’t just be copied: it is what the artists sees in it that matters. Hold these in mind as we progress through the lesson.

FROM THE ARCHIVE

The BBC has a wonderful archive of Henry Moore documentaries.

WATCH this excerpt from John Read’s documentary on Henry Moore. It was first aired in 1951 to coincide with the inclusion of a Reclining Figure by Moore in the Festival of Britain on London’s South Bank.

Notice how Moore discusses his interest in natural objects as a figurative sculptor. It is particularly interesting to hear how he relates this to his interest in what he calls ‘primitive art’, that is to say, art and antiquities from Asia, Africa and the Americas.

(If this clip won’t play on your device, access the full documentary HERE and watch from 06:50 – 10:04)

ACTIVITY

Take a moment to jot down what you think, using your own words. Why were natural forms and the landscape so important to a sculptor whose work primarily referenced the human form? You might find it useful to imagine that you are in our sculpture park with a friend who has asked you that same question. What would you reply? Your hunches at this stage are fine.

GALLERY

In the next part of this lesson, we’re going to look at two further bronze reclining figures by Moore placed around the Sainsbury Centre. Take a look at these galleries to familiarise yourself with them, before moving on to our Curator Podcast.

Two Piece Reclining Figure, No. 3, 1961

Draped Reclining Woman, 1957-58

CURATOR PODCAST – WITH TANIA MOORE

In this podcast, I spoke to our Chief Curator, Tania Moore. I asked her why she thought that Moore, an artist concerned with the human figure, was so preoccupied with natural forms and the landscape. What was it that Moore was trying to get at, or get away from, with his new visual language?

READING

Here is our first ‘long read’. It’s worth the time for those of you who would like to dig down a little deeper into Moore’s connection with European modernism. It comes from Alice Correia. In this catalogue essay for the Tate research publication, Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, she writes about an important predecessor of our Reclining Figure – the Recumbent Figure of 1938. It was made by Henry Moore for the architect Serge Chermayeff to stand on the terrace of his home overlooking the Sussex Downs. Correia uses it to trace Moore’s early explorations with the reclining figure out-of-doors in an art-historical context.

LINK to ‘Henry Moore, Recumbent Figure, 1938‘

ACTIVITY

As you are reading, jot down anything new that you learn about Moore’s interest in the natural landscape and natural forms. Where did that interest come from? How does he understand its relationship to the human form? How does that relationship help him to express what it is to be human?

OPTIONAL ASSIGNMENT

We have learned in this lesson that Moore drew on the forms and forces of the natural world to develop a new sculptural language, a language that helped him to express something immediate and universal about human experience. Returning to the first sculpture we looked at in this lesson, Moore’s Reclining Figure of 1956-62, write a short reflection on what you see in this sculpture? To what extent does it resonate with your human experience. You might find it useful to consider the following starting prompts:

- What is your eye is drawn to?

- How does it makes you feel?

- What does it makes you wonder?

- What does it reminds you of, or call to mind?

- What is it that you see – in the form and texture and so on – that makes you feel or think these things?

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS

For Henry Moore, generally, visit the Henry Moore Foundation website which has an extensive array of resources and further reading. https://www.henry-moore.org/

Another good place to look is the BBC website. They have digitised all of their programmes on Moore, and excerpts/full programmes are now available to watch in the BBC online Archive here https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henry-moore

Tate also have some really nice resources. You can find a general introduction here: Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986 | Tate And well worth a fuller browse is the excellent research project that this lesson’s reading comes from: Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity | Tate

For a biography, I’d recommend The Life of Henry Moore, Roger Berthoud, Giles de la Mare Publishers, 2003.

And for an anthology of solid scholarly essays looking at Moore from different perspectives: Henry Moore, Critical Essays, Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell, Eds. Ashgate, 2003

For an excellent, comprehensive collection of Moore’s own writings and interviews: Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Alan Wilkinson, Ed. Lund Humphries, 2002