Lesson Four – Frink Out of Doors

GETTING YOUR EYE IN

Take a close look at Elisabeth Frink’s Mirage I & II. If you have the app, you can launch the pieces in 3D and wander around the two sculptures in your own space, and scan their surroundings using the 180 degree videos.

Alternatively, take a look at the gallery below..

Don’t forget to give yourself time to look closely at the works. Let them come to you before you let the analytic part of your mind take over:

- What do you notice?

- How do they make you feel?

- What do they make you wonder about?

FROM THE ARTIST’S PERSPECTIVE

Take a look at these words and works by Elisabeth Frink. As you are reading, see if you can pull out five key words and phrases that encapsulate why Frink was motivated to site her work out of doors.

“I mainly think about sculpture for the outdoors, if I’m doing a big piece. Although I do like to see my big pieces inside confined in the gallery because it gives them a sense of busting out, which I quite like for a change.

…

My scale got larger when I moved to France because I had space outdoors there. Before I had a London studio and a small garden. I never had the opportunity.

British Library Sounds. National Life Story Collection: Artists’ Lives. Elisabeth Frink. 5/7. 00.15:30 – 00:17:00.

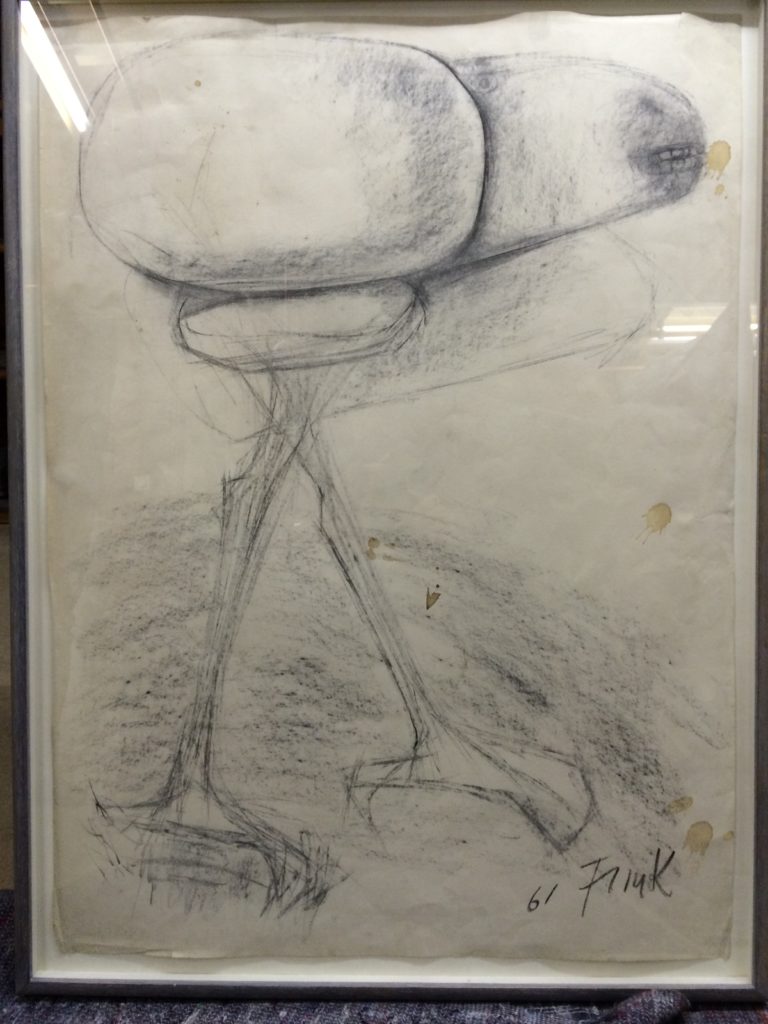

h. 530 x w. 286 x d. 132 mm

Provided to the Sainsbury Centre in accordance with the wishes of the artist’s late son, Lin Jammet

© Frink Estate

The very best I can hope to achieve is the feel of a man running or the movement of an animal in the landscape. Working in a landscape has become very important to me. I think my sculptures are about what a human being or an animal feels like, not what they necessarily look like. I use anatomy to create the essence of human and animal forms and their freedom of spirit.

Elisabeth Frink, 1979

Drawing

Provided to the Sainsbury Centre in accordance with the wishes of the artist’s late son, Lin Jammet

© Frink Estate

The Mirages – that was a strange theme. It really came from going to visit the Camargue for quite long periods. In the very hot weather people on horseback, or birds – flamingos in the distance – used to assume these strange, stalking shapes, floating, broken up in the distance. I think at the time I was trying to do something that was part bird, part stalking beast, but not entirely either. I just did three or four big ones and a series of small ones. They’re fairly abstract, compared with what I usually did.”

Frink: A Portrait, Edward Lucie Smith, 1994. P.123.

Firstly I am doing [sculpture] for myself, secondly I am doing it for other people to look at, of course; I think it should be outside as much as possible for that reason. It is important for people to come across sculpture as a presence because a 3-D object can be very telling; it takes up space and people can walk around it.

…good sculpture – either figurative or abstract – should stand well out of doors. Even small pieces look nice outside, funnily enough. It depends how you site them, whether it is in relation to trees, hills or tables, they can look good indoors and out.”

Elisabeth Frink in an interview with Normal Rosenthal, included in the 2015 Royal Academy Exhibition Catalogue, Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1952-84.

My five words/phrases were: Movement; freedom of spirit; relationships; presence; strangeness.

This video from the Lightbox includes some lovely footage of Frink, and her works, at her home, Woolland House in the Dorset Countryside. As you are watching, jot down any additional thoughts or reflections on the relationship of Frink the sculptor to nature and the landscape.

GUEST PODCAST

Coming back to a recurrent theme on this course: why might an encounter with Frink’s work out of doors still matter to us today?

Kaitlin Ferguson is an Associate Artist at the Sainsbury Centre. In her work, Kaitlin seeks to disrupt human-centric viewpoints. I asked Kaitlin about her interest in Frink’s work from the perspective of her own creative practice. Inspired by Frink’s comment that a work out of doors makes us ‘notice other things’, we took a walk to Mirage I and II and considered how it changed our perception of our surroundings. Given our current concerns about the environment, how important was it, I asked Kaitlin, to continue to encounter works like Mirage I and II in an outdoor setting?

READING

In this essay from the Human and Other Animals exhibition catalogue, Tania Moore explores Frink’s work in the context of post-war British culture. It’s well worth reading if you are interested to see how Frink’s approach is situated in relation to the wider social context that we explored in the first section.

Jot down anything you find interesting.

As you were reading, you might have spotted some of the themes we explored in the earlier lessons, and noticed how these continued to evolve in the post-war period. For example:

- the persistence of natural forms and subjects in the work of the ‘new generation’ of British sculptors, including Frink,

- the ongoing commitment to showing work out of doors,

- the continuing focus on social regeneration and access to the arts,

- the prevailing shadow of the war on the individual and national psyche,

- the use of figurative and expressive elements alongside experiments with abstraction, geometric forms and industrial materials and techniques.

OPTIONAL ASSIGNMENT

I asked Kaitlin to curate a creative assignment for this lesson. Her brief was to design an activity that, taking inspiration from Frink, would help us to really tune into our surroundings, and change our ways of looking at and relating to a familiar environment.

FURTHER EXPLORATION

If you’ve been inspired by Kaitlin to further explore ideas around the anthropocene and our entanglement with nature, Kaitlin recommends the following which she has found transformative: Robert Macfarlane’s Underland of 2019, David Farrier’s Footprints of 2020, and Anna Tsing’s, The Mushroom at the End of the World of 2015.

You can aslo find a number of filmed interviews and dodumentaries online. These offer some wonderful footage of Frink talking about her work, and her studio and gardens at Woolland House. These tend to come and go, so if the links below no longer work, try typing ‘Elisabeth Frink’ into your internet browser, and searching under ‘video’. Some lovely snippets from the archives will generally show up.

At the time of writing, these videos are available on Youtube via the following links.