Lesson Seven – Ian Tyson’s Proximity

INTRODUCING IAN TYSON

Ian Tyson was born in 1933, in Wallasey in Cheshire, and grew up in Upton near Birkenhead. After graduation, he worked in the shipyards as an apprentice engineer but, realising that his ambition was to be an artist, he continued his art studies at Birkenhead School of Art and the Royal Academy Schools.

Tyson taught at many institutions including Farnham School of Art, St. Martin’s School of Art, and Wimbledon School of Art. He was awarded a Brinkley Fellowship at Norwich School of Art from 1979–80. He also taught as a visiting professor at the Royal College of Art, the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and the University of California at San Diego.

Tyson is better known by some for his artists’ books. He founded the publishing imprint, Tetrad Press in 1970, and ‘Ed It’ which he founded five years after Tetrad closed in 1995. He collaborated with avant-garde poets, illustrating, or perhaps better to say, accompanying their poems with abstract imagery that responded to the tone and structure of the text. He often worked with young, up and coming avant-garde poets, and also with established poets such as his long-time collaborator, Jerome Rothenberg.

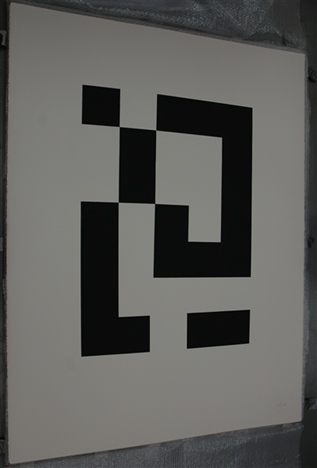

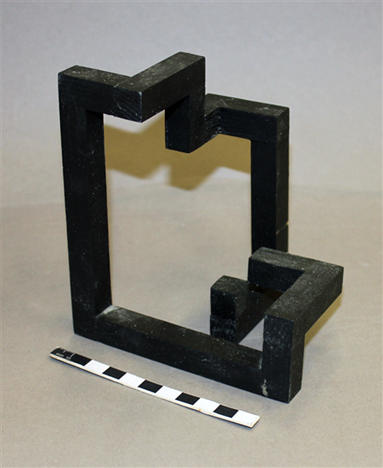

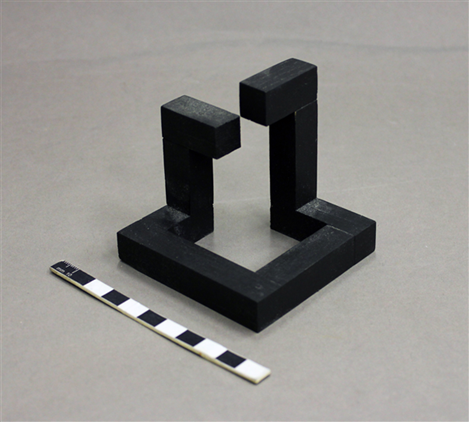

Tyson also made an extensive body of collages, reliefs, maquettes and sculptures. Talking about his own career, Tyson said he started out mainly producing paintings and some collages, then mainly collages and some sculptures, before moving into larger scale sculptural works later in his career.

His earlier sculptures were made in wood, but after making friends with a welder who lived near him in Vaucluse, France, he was able to realise his ambition of producing larger scale works constructed from metal. In later interviews, he spoke of how this took him back to his formative experiences working in a shipyard where he first discovered a passion for making.

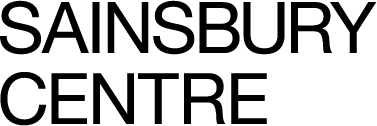

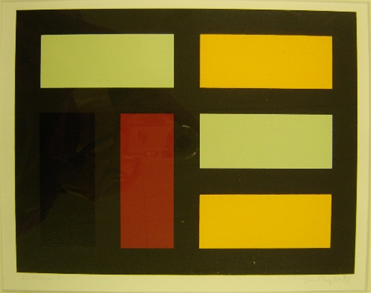

Tyson had a long-standing fascination with geometry and mathematics, and experimented with the endless possibilities of horizontals and verticals composed into a grid. He was keen to point out that the systems he used – starting with five rows of five squares, for example, then experimenting with placing blocks of colour into it in various configurations – were only starting points, and he worked instinctively to find what was most visually interesting. He would then take what he had learned as a starting point for the next sequence of images. This preoccupation with the grid continued into his sculptural work, which he saw as a three-dimensional extension of his earlier ideas expressed in painting, printmaking and collage.

He exhibited in many group and solo exhibitions across Europe during his career, and his work is now held in a number of public collections including The Tate Gallery, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Council and the British Library who hold The Ian Tyson Collection. Works by Ian Tyson in the UEA Collection include his prints, collages and maquettes, as well as the steel sculpture, Proximity, that we’ll be looking at in this lesson.

GETTING YOUR EYE IN

Now that you’ve been introduced to the architectural setting of the campus, let’s take a closer look at one of our sculptures that sits right on the border between the campus architecture and the parkland: Ian Tyson’s Proximity.

As always, if you have the app, do have a virtual wander round the sculpture in AR, and use the 180 degree videos to get a sense of the work in its setting. Alternatively, use the image gallery below.

Jot down what you notice as you move between the different viewing positions,. What kind of visual echoes and contrasts do you see as the vista shifts?

ACTIVITY

Tyson said: “I’m more interested in things which make questions than provide answers.” What questions does Proximity ‘make’ for you? Jot them down.

Now take a look at what the artist himself says. Does this answer any of your questions, or raise new ones?

FROM THE ARTISTS PERSPECTIVE

The maquettes are really three-dimensional manifestations of a lot of work on paper: the two-dimensional things were taken into a totally different direction. It’s almost as if you took a two-dimensional piece and you kept turning it and adding another piece onto it every time you turned it, and then you would end up with a three-dimensional piece.

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, Part 59.

I was very interested in the juxtaposition of formal and informal things, but I never found out how you solved it. For example, you could get a resolution in some Japanese and Chinese house, where you look through very formal architecture into the garden, which is the informality… How you make that work in the terms of Western art, I don’t know. I’ve certainly never done it… If it happens, then it would happen through very carefully constructed pieces of sculpture that you could see through. And if they were in that sort of landscape, that you would see the landscape through them, then I think that would be the resolution.

(From an interview made before the commission for ‘Proximity’.)

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, Part 18.

Sculpture

I thought, what this sculpture has to do is reflect the essence of these two buildings, plus the essence of the environment in which it’s going.

It’s basically a space frame, following a drawn line, and it takes different tracks and at one point it goes up in steps and turns round the corner to a step which reflects what happens with the rooves of the ziggurats and then, when it comes back on itself into the large open spaces of the space frame, it reflects the open-endedness of the Sainsury Centre. And then, when the two points, the starting points and the finishing point of this open frame, get together, they don’t meet, they offset against each other and their two points, so they just miss meeting each other and that gives the whole thing a sense of incompleteness ….

(From an interview made after ‘Proximity’.)

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, part 65

Ink, Paper

There are some parts where you look through the sculpture at the ziggurats and its almost as if you’re looking through something fragmented – you know, like when you look through one of those little kaleidoscope things…and then you’re walking around and that particularly part of the sculpture….what your looking at is the space between the other elements and the open end of the Sainsbury Centre. And all the sculpture is doing at that point is reflecting the squared off end of that. And then, when you walk round a little bit more, when you look across the meadow towards the lake and the trees, what you have is a much more open vista. You can see right through the sculpture at this point and that’s really important because the sky is extremely important there.

The name Proximity…was decided before it was finished, in the maquette stage, because the ending was approximate where the two pieces meet.

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, part 65.

What I found when I moved into using geometric shapes, and this sort of totally abstract composition, was that although there were imposed parameters – if I’d decided to use a sequence of squares within a square, for example – the number of permutations of the usage of that is almost infinite, and therefore within those established parameters, you have immense freedom to move around. Much more freedom, in fact, than when I felt that I could do whatever I liked.

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, Part 33.

I like the architecture, and I see that I could do something that would relate to the architecture there, because on one hand you’ve got the Sainsbury Centre designed by Foster, and on the other hand, you’ve got the student halls of residence designed by Denys Lasdun, and, OK, you certainly can’t come up with anything insignificant to shove between these two, but if you take the challenge up, it’s not a bad backing group. So that’s why I wanted to do it.

…

The end view of the Sainsbury Centre and the running walls of the ziggurats are approximately at right angles, so I’ve taken a line off the ziggurats…and where it intersects is where the sculpture is going to go. So it’s on this meadow, that outspreads from the ziggurats and the Sainsbury centre right down to the lake and woodlands, and its in a very nice position. You can see it from the end of the Sainsbury Centre, and from the Ziggurats, and as you approach the meadow from anywhere in the university…so it’s a prime position.

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, Part 62.

I began to see that if I had the two ends of the drawn line, …if they ended up with one unit of space between them, and they were juxtaposed in some way – either one unit behind each other, or one unit to the side of each other – you got a strange tension between these two ends. It’s almost like a spark would jump across them. And then it also began to work into my notion of the intervals that I like in music where you get an unexpected silence… And that silence is also a note, its also part of the music. And that’s the discovery I made when I chopped this one up [an earlier sculpture that Tyson reconfigured], I could get these two elements near each other, in proximity, and that provided another kind of tension…That’s what I’m interested in, the tension between these points.

And the area that it encompasses being open, you see different vistas through every little bit of the sculpture as you walk around it.

Artist’s Lives, British Library Sound Archive, Part 59.

Silkscreen, Ink, Paper

CURATOR PODCAST – WITH CALVIN WINNER

Lets come back to our question about what makes the University of East Anglia campus a distinctive setting for modern British sculpture. I went on a walk into the park with Calvin to look at Proximity. Drawing on his curator’s eye, I asked him how well he thought it worked in its current location, and what he made of it on a personal level.

As you are listening, notice the different factors Calvin takes into account when considering what makes a particular placement of a sculpture successful.

AN ARTIST’S PERSPECTIVE

Instead of a reading for this lesson, I invited Ian Brownlie, Associate Artist with the Sainsbury Centre, to share his own thoughts on what makes this piece so interesting. I was interested to know what Ian, as a practicing professional artist, finds in a work like Ian Tyson’s Proximity.

OPTIONAL ASSIGNMENT

As Artist Ian Brownlie showed in his video, it is possible to find endless possibilities within the deceptive simplicity of Ian Tyson’s Proximity I asked him to curate an activity that would help us to develop our own creative relationship with the piece.

If you’re not an artist, don’t worry, it’s the process that is important. It’s all about different ways of looking and thinking through a visual process, rather than with words. Why not give it a go?! Then come back to Tyson’s proximity and see if you view it differently.

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS

If you’re interested to learn more about Ian Tyson, and the British art scene generally at the time that he was working, the British Library sound recordings are a wonderful resource to browse. https://sounds.bl.uk/Oral-history/Art/021M-C0466X0063XX-0001V0

We have a good collection of Tyson’s work in our collection here at the Sainsbury Centre which you can explore on our online catalogue here

Bridwell Library Special Collections also have an interesting collection of Tyson’s work and you can find a nice tribute to Tyson here