Lesson Nine – Antony Gormley’s Another Time

ARTIST’S BIOGRAPHY

Antony Gormley was born in London on 30 August 1950. His mother was German and his father of Irish descent. He grew up in Hampstead, the youngest of seven children. He attended Ampleforth College, a Benedictine boarding school in Yorkshire. Gormley read archaeology, anthropology, and the history of art at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1968 to 1971. After graduating, he travelled for three years in India and the Dominion of Ceylon/Sri Lanka to learn more about Buddhism. It was during his travels that he saw people covering themselves with a piece of cloth in public, something which inspired his first plaster casts involving the human form.

On his return to London in 1974, he studied at the Central School of Arts and Crafts (now Central Saint Martins), and Goldsmiths College. He moved on to postgraduate study at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1977. It was there that he met Vicken Parsons, a successful artist in her own right, and later his wife, who would become his primary assistant. For the first fifteen years of Gormley’s career, Parsons carried out all the moulding from Gormley’s body, allowing him to make the life-sized naked figures that have become a distinctive feature of his work.

His first whole-body casts were made in 1981 for Three Ways: Mould, Hole and Passage. During this period he experimented with various materials and with various positions of the human body: crouching, standing, kneeling, lying. Already evident were his enduring fascination with the relationship of the body to its environment, and the reciprocity between the sculpted figure – made from his own body ‘from the inside out’ – and the body of the viewer. In the same year, Gormley’s first solo exhibition took place at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. By the end of the decade he was exhibiting internationally.

Gormley came to mainstream public attention in 1994 for his installation work: Field for the British Isles, composed of tens of thousands of small terra-cotta figures, massed within a single gallery room and facing the entrance where the viewer stood. The figures were made with communities around the world.

In the later 1990s, Gormley began siting his naked life-size figures out-of-doors. This began a new line of philosophical reflection: about the relationship between sculpture, viewer, and man’s place in this world and the wider cosmos. For Another Place, made in 1997, Gormley placed 100 cast-iron figures over a two-mile stretch of Crosby beach in Merseyside, all facing out to sea. The following year he completed one of his most famous and iconic works: Angel of the North, near Gateshead, England, which stands at sixty-five feet (twenty metres) high, and has a span of one-hundred-and-seventy-five feet (fifty-four metres). By the end of the decade, Gormley’s position in British art and life was firmly established. He was created an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1997, and received the South Bank Prize for Visual Art in 1999.

Gormley became a Royal Academician in 2003. More prestigious exhibitions and accolades followed, including a show at the Hayward Gallery, London, in 2007, and the Bernhard Heiliger Award for Sculpture which he was awarded in the same year.

Also in that year, Gormley created Event Horizon: thirty-one life-sized and anatomically correct casts of his body, four in cast iron and twenty-seven in fiberglass. These were installed on the top of prominent buildings along London’s South Bank. In 2008, The Daily Telegraph ranked Gormley number four in their list of the “100 most powerful people in British culture”. Further media attention followed in July 2009, when Gormley presented One & Other as his commission for the ‘Fourth Plinth’ in London’s Trafalgar Square. He invited members of the public, chosen by lot, to spend one hour on the vacant plinth as ‘living art’. The event was discussed by characters in the Archers, a long-running BBC radio drama series, with Gormley appearing as himself.

Gormley continued to experiment with life-size figures in public spaces, often building on previous projects. For 6 times, for example, (2010) he placed six figures along the Water of Leith in Edinburgh, one at the end of the pier facing the sea, one partially buried on land, and four partially submerged. In 2010, he installed Event Horizon – a project originally conceived for London’s South Bank – in the Flatiron district of Manhattan. This saw thirty-one sculptures placed around the Madison Square Park area, some at ground level and others on rooftops and ledges, and later (2010) in locations around New York City’s Madison Square . In this way, Gormley sought to ‘activate the skyline in order to encourage people to look around. In this process of looking and finding, or looking and seeking, one perhaps re-assesses one’s own position in the world and becomes aware of one’s status of embedment.’ The New York City Police Department had to reassure the public that the sculptures were not real people about to jump.

2012 saw another shift in Gormley’s work when he began to experiment with what he called “digital-cubism”. This involved creating human forms in an array of different postures and poses through the arrangement of solid steel cubes. For his exhibition, “Expansion Field” (2014) in Bern, Switzerland, he made sixty large-scale steel cubist figures. The making of these works was captured in an episode of the BBC Four series What Do Artists Do All Day?

A key feature of Gormley’s work is his permanent placing of sculptures in the landscape, where they are subject to the changing elements and geography of the site. For example, in May 2015, five life-sized sculptures, Land, were placed at points representing the centre and the four compass points of the UK: Lowsonford (Warwickshire), Lundy (Bristol Channel), Saddell Bay (Scotland), the Martello Tower (Aldeburgh, Suffolk), and Clavell Tower (Kimmeridge Bay, Dorset). The Dorset sculpture was knocked over into Kimmeridge Bay by a storm in September 2015. Meanwhile, on 6 September 2015, Another Place had its tenth anniversary at Crosby Beach in Liverpool. Talking about the work, Gormley commented:

Every time I’m there, just like any other visitor, you’re encouraged to linger a bit longer seeing the tide come in and how many of them disappear. And then you’re encouraged to linger further until they’re revealed again.

In 2019, Gormley exhibited on the island of Delos, siting 29 of his bodyform sculptures across the island, some among the archeological and geological features of this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Also in 2019, the Royal Academy held a major exhibition of Gormley’s work. Since then he has continued to exhibit around the world, including Singapore, USA, Hong Kong, Germany, France, Korea and the UK.

GETTING YOUR EYE IN

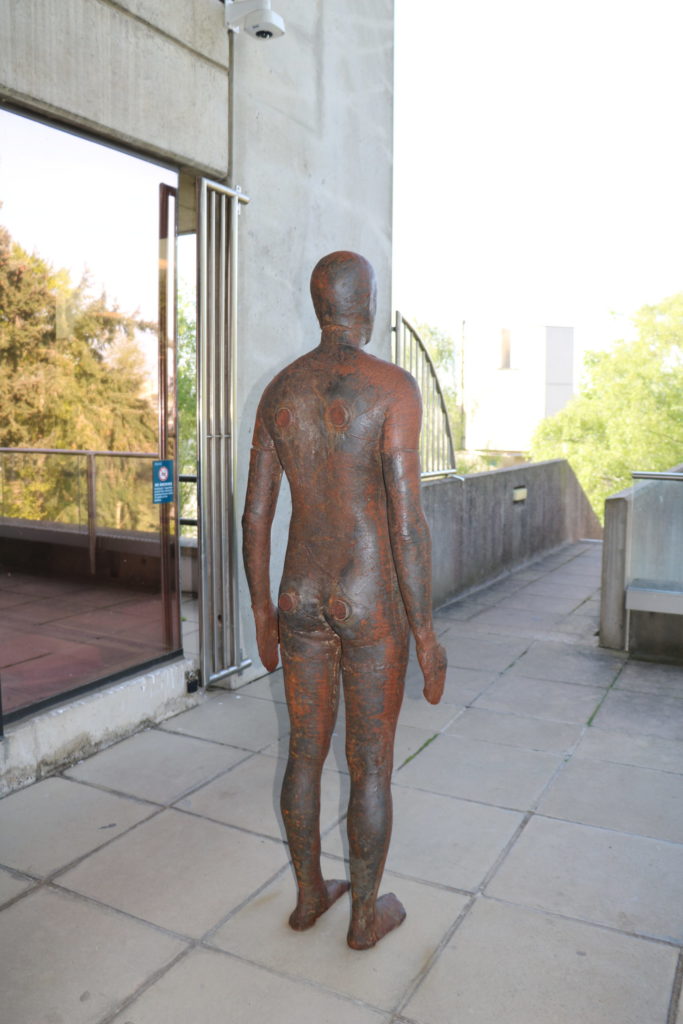

Take a look at this figures from 3x Another Time that stands outside the university library.

Give yourself time to notice the surface detail. You can right-click on individual images and open them in a new tab to really zoom in on detail. Think, too, about how the work is framed by the architectural setting, and the parkland visible beyond. Imagine how it would feel to turn the corner, or come up the steps, or come out of the library and encounter this life-sized figure.

Don’t forget to use the app, if you have it, or you can work from the image gallery below.

ACTIVITY

Think back to our architecture tour of the campus. Try to imagine how people are moving around in this space as part of their daily lives as staff, students and visitors to the campus. What do you make of the location of the piece in the heart of the UEA Campus?

Note down your initial reactions to the sculpture in its current location.

FROM THE ARTIST’S PERSPECTIVE

Take a look at this collection of quotes from Antony Gormley talking about his work. As you are browsing, think about the key things that he’s trying to ‘get at’ in his work.

“The whole idea of escape is countered by the work’s persistent and repeated presence: there isn’t another place. We only have this place and this is what we have to deal with, the here and the now, the changing tide and the changing light and the feeling of the mud squeezing up between your toes and the fact that yes there is a horizon that is our perceptual limit: that is the reality halo. The work (ANOTHER PLACE) reinforces primary physical experience, the weight of your own body, the pressure of earth pushing up against your feet, the passage of air around your body, against inscriptions of pure ideas. I want to ground things in the present and acknowledge the fact that we live in an industrial, man made world. Another Place and Critical Mass are both very insistent about their nature as industrially produced mass-produced surrogates for the body.

“I accept elemental nature, but I accept also our absolute responsibility in changing nature. We are the toxic extension of natural systems.’

Interview with Iwona Blazwick, Director of Whitechapel Art Gallery, for Some of the Facts, Tate St Ives

“I think that for me the challenge of our times is to recognise that culture is an extension of nature: that art is a part of a natural system which leads us back to our nature in nature.

I want to recapture that sense of imaginative space inside the body. I want there to be an internal pressure in the work, that has a relationship with the atmosphere which we sense with our bodies through the skin of the work.”

Interview with Declan McGonagle

“I think you could identify my project as a whole as a return to the body not as object but as place”.

From: Field for the British Isles, pp. 76-77, and p.80

“I think of my work, certainly in its first phase, as being a kind of architecture. It’s a kind of intimate architecture that is inviting an emphatic inhabitation of the imagination of the viewer.”

“I want the works to be reflexive. So it isn’t simply an embodiment of a feeling I once had. It’s a meeting of the expressiveness of me, the artist, and the expressiveness of you, the viewer. For me the charge comes from that confrontation. It can be a confrontation between the movement of the viewer and the stillness of the object, which is an irreconcilable difference, but also an invitation for the viewer to sense his own body through this moment of stillness.”

“The history of western sculpture has been concerned with movement. I wish to celebrate the still and silent nature of sculpture. The work is designed to be placed within the flow of lived time. Recently, the works have been placed high on buildings against the sky, standing apart from the shelter and protection of architecture.”

Antony Gormley in conversation with Ernst Gombrich.

“I treat the body as a place encouraging empathic occupation of that which lies the other side of appearance: what it feels like”

Now watch this video from the lovely Tate Shots series, that gives a wonderful insight into Gormley’s working space and processes, and his thoughts on the deeper meanings of his bodycast figures.

GALLERY

In the rest of this lesson, we’ll be looking at all three of the figures from 3x Another Time here at the University of East Anglia. Take at look at this gallery showing the other two sculptures in their rooftop locations – one on the roof of the teaching wall, one on the library roof, to get a sense of how they are positioned across the central campus complex.

CURATOR PODCAST

Now listen to this podcast with Calvin. I asked him about the thinking and decisions behind the siting of 3x Another Time at UEA. I was curious to hear more about Gormley’s close involvement in that process. As you are listening, add to your notes anything that you find interesting or relevant.

READING

I really like this essay by Stephen C Levinson. Notice how his anthropological lens leads him to explore Gormley’s cast figures in a really distinctive way.

ACTIVITY

Taking inspiration from Levinson’s essay, try the following activity:

Stand (or sit if you prefer). Take a few deep breaths. Feel the surfaces of your own skin. Notice where you can feel your own skin between your fingers or toes, where you are aware of the joints against the inside of your skin at your knees and elbows, your shoulder blades, the sensation of your own scalp, your ribs rising and falling as you breath. Now think about your sense of an interior space: a sense of yourself, an individual, a human consciousness, – with thoughts, feelings, an imagination – inside a body. Now think about how your interior self inhabits an exterior space through your senses.

Think about your sense of orientation in the space where you are standing or sitting. What is in front, behind, near, far. What is within arm’s reach? What would require you to walk to fetch it? What is left and right. Turn, and feel that left/right orientation turning with you.

Now think about the difference between approaching one of the body casts from Another Time from behind, or approaching it face on. Imagine standing with your back to the figure. Think about how it looks, or doesn’t look, back at you. Think about how different your encounter might be if these figures were sitting, kneeling or crouching? How might that change the meaning of the work and your response to it?

You might want to return to your initial notes from the first activity in this lesson, where you reflected on your initial response to the Another Time figure in the heart of the UEA campus. Having read the Levinson piece, is there anything you might add?

OPTIONAL ASSIGNMENT

For this activity, start by watching this short video of Gormley talking about Another Time, in this case, for a project at Folkestone where the figures would be looking out over the sea.

Let’s go back to the claim that Gormley makes in this video, that his sculptures are not really art at all until they are sited and viewed. Taking this as a starting point – what might you bring to them as a viewer? Write, or if you prefer, record, a short reflection that brings them to life as artworks – good or bad – through your response.

It might also be interesting, if you have the app, to play at ‘siting’ the piece, using different scales to suit the setting. You could play with indoor and outdoors settings – confined spaces and outdoor spaces. Move around the piece in each location, noting your thoughts and feelings. How do they change according to their scale and placement?

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS

If you want to find out more about Gormley, the best place to head is to the artist’s official website: Antony Gormley This gathers together all the publications and videos on the artist.

There are a lot! So here are a few recommendations for starters:

This video from the Brilliant Ideas series. At the time of writing, you can find it using the embedded Youtube link below.

A conversation between Antony Gormley and the famous art historian, Ernst Gombrich. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/gormleyandgombrichinconversation-gormley-gombrich-art

And this extensive interview with Declan McGonagle: https://www.antonygormley.com/resources/interview-item/id/132

I also like LAND, The Landmark Trust, 2016. Author Jeanette Winterson and photographer Clare Richardson travelled to remote locations to see Gormleys life-size cast iron sculptures. Winterson reflective text is accompanied by Richardson’s photographs.